A guest blog by composer Wang Jie

Almost all musicians cocoon their mistakes behind practice room doors. When they walk on stage, their bow marks the beginning of truth, and beauty, and butterflies. I’m a composer. I make all my mistakes in public, in front of musicians I admire, people I care about. Still, after each performance of my work, I’m invited to appear on stage to take bows. Nine out of ten of these performances are world premieres. I will have just greeted the result of months, sometimes years of gestation and labor. As if emerging from hand combat with death, I couldn’t care less about having won or lost. I’m just thankful it’s over. My first bow is to thank the musicians for their effort, knowing they all can name the problems in my work but have played their hearts out anyway. Then I turn and bow to thank the audience for giving my work 15 minutes of careful attention. Every bow is sincere, and my bows look good, because the revered composer Christopher Rouse taught me how to bow on stage, always from the hip. Even so, people keep telling me that I rush off stage when the applause is going strong. I’m not being rude. Of course I want that good feeling of accomplishment, but I notice someone missing: the Muses who once commanded me to compose this piece. They are nowhere to be seen. I long for a different kind of bow, to my Muses, when they eventually return, nodding from above the balcony as if to say “you did OK, kid.” But when they don’t, I feel orphaned. So I tell myself I’ll fix things up for the next performance. Will they come then? I know as well as anyone that today, second performances are few and far between, even for the big name composers. That’s when I lose control of my feet: I’m so disappointed by my own creation that I can’t stand to be seen with it a second longer. I can’t change this impulse. I don’t know how. For the last twenty-eight years and 40 – 50 compositions, I’m still rushing off stage, with no end in sight.

I wonder how other composers survive without a cute white dog. I have, among my most valued possessions, Pilot, an exceedingly rare Sealyham Terrier. She is the cutest white dog of all dogs. Even before Pilot, I got my pep talk earlier than most.

"Don’t become me. You’ll never make money. Never be famous. Nobody cares and anything else is easier.” My first mentor, Yang Liqing, was then the head of the composition department at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. He did what any good composer would do: he tried to talk me out of it. "You are a good looking girl. You have options.” I worshipped him since my very first weekly lesson at his French style brownstone shortly after my 4th birthday. Even his giggles were endearingly musical. He was my hero. I was determined to become his clone, giggles and all. So instead, I misheard him to say: “You’re a good looking girl. You have options. You can become a composer just like me.” It wasn’t long before Manhattan School of Music offered me a scholarship to study composition. Amused by my excitement, he hid a grin behind his cigarette and said, “Stay away from 125th Street, free drugs, and first rehearsals. I didn’t make it through my first rehearsal in Darmstadt.” He paused to puff, “I ran out to puke.” I never expected to hear this from him. Partly because he had put up with me once a week for fifteen years. And when I acted out, I threw thorny tantrums. He had the toughest skin. He was immune to all the bad behavior in the world. Nothing ever got to him. Between a grin and a giggle, he just kept on teaching me and composing whenever he could.

Although we mostly worked on my piano skills, because that’s what my parents paid for and I obeyed, my occasional relief from duty was pretending that I was him, composing a little something about a couple of rabbits, one of them racing a turtle. I must have been five when I finished a music score for the first time. Even then, I reveled in the secret pleasures of fiction. I saw myself dotting music notes on luxurious manuscript paper glowing in warm lamplight, chasing away fifteen winters. Puking just didn’t fit that picture. So my entrance to the formal training at Manhattan School of Music was marked by a sort of blind competitiveness. I have been taught by the toughest. I’m sure I can do even better!

With that attitude, I arrived at my first New York rehearsal, a piano trio that ended with a slow movement pedaled by pretty chords. My mentor this time was Richard Danielpour. We began our 17-year-friendship that evening, on his gentle suggestion that a tempo with a bit more motion could be all the last movement needed to take shape. He asked the musicians to demonstrate. With each stroke of the chords, faster, my chest responded with increased spasm. I held on for as long as I could, then excused myself from the rehearsal. I ran to the nearest restroom and sobbed uncontrollably. I thought a ghost had just assaulted me, trying to rip out my entire rib cage one bone at a time. Richard and the musicians were right: the pedaling chords would have sounded too mechanical. It wasn’t breathing. How could it be so dead on paper? I didn’t recognize my own creation as soon as it had been played.

All serious composers agree that the only way to learn is to get the work in front of other musicians. Their time, artistry, attention, plus the public, the concert hall, the administration that pays for them all, the generosity of donors, established composers, the entire village has to show up for a composer to secure any meaningful practice. Practice, practice, practice. In all music disciplines, practice is the lifeline. In a way, composing is all about revising. Composers write alone. That’s like a musician without an instrument. Composers’ real practice begins at first rehearsal. Lots of problems surface; for example, a chord that sounds perfectly resonating on my piano shrivels in a string quartet. A melody that sounds lively in my head can cause a flutist to dial 911. On other occasions, it’s a funny feeling: wow, these musicians can play all those other notes too! But once the musicians have learned their parts and rehearsal has begun, only minor adjustments are realistic. Sometimes the musicians ask questions, and I stand there like a deer in headlights. That’s because I am just thrilled to hear my notes flying off the pages, but I’m choked with regret. Oh, for God’s sake, revise revise revise. In the first decade of my career, I did not secure performance opportunities for my revisions. Not that I didn’t try hard. I feel tremendous empathy towards my struggling students, because the pressure of getting it right the first time used to paralyze me too. Samuel Beckett wrote: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Under the best circumstances, and I have often had the best circumstances, I have clocked in three or four performances a year. They total less than an hour of public music.

Hundreds of hours of private labor distill to one hour of time in performance. Although invisible to the public, this is an undying theme of a composer’s life. There is no other way to go. We are mortals and these are our challenges. We are “stone stuff” programed at the ground level. For a long time, our sense of time has been carved into units of years, months, weeks, days, hours, minutes and seconds. One hour costs 60 minutes. Can’t argue with that. We now know enough about physics that we are so “grounded” in our time zone, we don’t feel the speed at which all of us are traveling in the galaxy. Up above the ground level, where the Muses live, however, the experience of time changes. And I can prove it.

Wednesdays, I drive to my teaching job at Brooklyn College via the Westside Highway. Something about driving alone in total silence, at 60 miles an hour, puts me in the wavelength of my Muses. Right about when I hit the third light at Chelsea Piers, almost without exception, I hear a new symphony in my head. When traffic is bad, I hear a new opera. They flash by in a split second, complete with detailed orchestration schemes, narrative arcs, real beginnings and endings, several solutions to the climax. I’m unable to dictate all that information in one sitting; I spend the rest of the commute bemoaning that I’m stuck in this forgetful, limited, distracted, meat sack of myself. By the time I get home from teaching, only a shell of the magic remains. I spend a few hours notating a pathetic page or two of what appears to be two seconds of music in actual performance. I’m tired, hungry, and frustrated with the entire process. When I have something good to eat, I feel blinded by confidence. I’m gonna’ nail it this time. More often than not, I pray musicians will not be appalled when they play it through for the first time. I hope people keep judgements to themselves, because I know better than anyone that my piece, despite having a finished double barline, is a work-in-progress, nowhere near its perfect form which came to me driving to Brooklyn. Wednesday after Wednesday, hours of musical grace unrecorded. Over the years, my Muses must have endowed me with a dozen symphonies in embryo, several operas unhatched. Even at 60 miles an hour, I will never be able to catch up with them. Sometimes I cry out of sheer exhaustion, desperate for sightings of them. I want some kind of confirmation that I’m on the right track. I want them to be proud of me.

Like so many before me, I realize the inadequacy of my skill. The music I write is so much better in my imagination. There are times when my peers and I loathe composing. Can you blame us? It’s a choice between bad, worse and worst. If you think my frustration is extreme, imagine not hearing from the Muses, ever. The worst, and I don’t say this lightly, is having watched many of my colleagues quit composing. All my students, at some point or another, have asked me: “What, then, keeps you going?” Because I love music, I used to say. That’s true of course, but that’s also why some quit. If you sit me down with a glass of wine and ask me again, I will confess that I’m hooked on the best drug ever.

If you sit me down with a glass of wine and ask me again, I will confess that I'm hooked on the best drug ever.

Some call it the “flow” and there is a whole book about it. Stravinsky used to call it “the appetite.” You’ve got to wake up every day and want to hunt down those notes before they get away. You’ve got to have the techniques whenever you need them, and you must control them effortlessly. You’ve got to work hard year in and year out. But working hard doesn’t guarantee “flow.” If you can find a composer who’s earned a taste of “flow” and then quit, now that would be newsworthy.

If you upgrade me to a single malt, I will tell you that the people I love have loved me back. There is no creation without a tradition and a community that supports it. Yang Liqing knew me well enough to pull a reverse psychology trick. That’s love. Every mentor I’ve worked with after him has been nothing but generous, supportive and encouraging. And the composers who are no longer with us continue to mentor me through their music. I hear their voices welcoming me: “You are one of us.”

And if you keep that single malt coming, I might start to sound like a snob, because on any given day, I am tremendously privileged to be doing what I do. I get to wake up in the morning and search for the optimum sonic solution to each little burp of my imagination. When work is going well and the stars line up, I get to touch the divine, kiss the hand of angels. It’s like defying death. I belong in a boundless kingdom, a realm of absolute freedom. Access to this realm is only possible through love and “flow,” which no amount of fame and fortune can purchase.

But the stars rarely line up. Even when they do, I receive no warning but I have to be ready. Being ready means showing up everyday, enduring the solitude and uncertainty the work demands, the slow drip of one average day after another. When I eat well, I imagine my Muses feasting too. Just as I hunt music notes, they flock to each whiff of “flow”, every spark of true love. Just as a serving of bok choy nourishes me and I find it so very delicious, the muses are nourished by the best of our spiritual production: a language that all humans share – the language of art. I believe they flock to me whenever I reach “flow.” I believe they find my sparks of true love so very delicious.

But I’m not that kid anymore, content with fiction under a warm lamp. I have to believe the Muses fervently want me. Today, I check the loathing at my studio door and compose with Pilot at my feet.

That would have been the picture-perfect “composer at work,” except no composer can survive alone, even if the dog is a cute, fluffy white Sealyham Terrier. I might be favored by the Muses, but I’m not them. My process and the obstacles which accompany it, are rooted in humanity. The Muses have not provided instruction. We are not assembling Ikea furniture in my house. Lacking multiple performances, most works in my catalogue remain dormant in their infancy, waiting to be revivified. Although I tell myself that channeling the Muses’ magic into the ears of this world has never been about creating perfection, it’s hard to look at my catalogue and not see it full of flaws that I am personally responsible for. Each time I start a new work, I am a stronger composer by the finish line. Even so, I haven’t yet found a way to love my own works the same way I have been loved.

From the debut of a music idea, the rigor of labor to the final push of birth, completing a composition is a maternal process, a force of mother nature. Becoming a composer is only possible through resilience and grit. If the fruits from our creative tree are indeed food for the Muses, I doubt they care whether you are male or female, gay or straight, young or old, or a bedridden invalid with one blinking eyelid.

I have chosen to follow my Muses and become a composer. My resilience and grit versus all kinds of quit. I owe this resolve to people who have paved the path, who took a chance on me. While some people may judge a book by its cover, I’ve been fortunate to have worked with a number of organizations that stood by their commitment to the music and its artists: you can hear a lot by just listening. I may look like a female, Chinese composer, but I am not a genre. I allude to the Western canon, Germanic avant-garde, Peking opera, Hindustani music, Afro-Cuban, and many shades of international, historical influence. These organizations have taken note of how I drive a stick shift of cultural variety with conviction, skill and fun. There are lots of us out there.

Even in the arts, a supposedly small and exclusive community, bad behaviors are no less unnoticed. I’m painfully aware how many men and women in my field simply didn’t have my fortunate circumstances. I haven’t been hit by a #MeToo incident. I have not had a commission that demanded me to express anything I don’t believe in. I have not met an audience which was not gracious and accepting. If I think really hard, I’ve been bullied exactly once, by a Chinese camel. It didn’t like the ringtone I composed for my Nokia, so it spat in my face. I’ve been tremendously lucky that the battles I have had to fight so far have been aesthetic ones. I get to act like the aesthetic divide in classical music constitutes the only warfare worth fighting about.

It troubles me to see how many of my colleagues did not get the nourishment they need. Many are equally hardworking, as driven as I am. It troubles me even more to see so many organizations understaffed, people who devote their work to support living composers are generally underpaid. The only reason I got anywhere in my career is that someone sitting on a panel, somewhere, decided to cut me some slack. I am far from ungrateful. But I worry every time the word “great” is the default adjective used to sell a classical concert program. I worry people who program these concerts can no longer afford the time or mental space to listen. More often now, political battles and box office incentives outrank aesthetic investigations. My ears hurt when words like “products” fly across conference rooms like popcorn in a movie theater. I worry one day I’ll find a crushed kernel left on the floor and it will be one of those pieces of my rib. I worry that the praiseworthy folks, those who have cultivated real listening, are not worth a click. As always, bad news gets the clicks. I worry also when I experience exemplary collaborations, such as my recent trip to the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, that it will never happen again.

Except for premieres, orchestras don’t normally budget for living composers to attend performances of their works. The BPO did. When I arrived at my first rehearsal, Conductor and Music Director JoAnn Falletta gave me the podium for a two-minute introduction.

That’s all it took: invisible barriers, assumptions, and doubts suddenly converted into collective trust. It was obvious the musicians love her. Any composer she wants to work with is all right with them. I didn't just feel it. I knew if I were going to make a mess anywhere, I could do so safely on that stage. Sure enough, the fifth (!) revision of my “Symphony No. 1” was still littered with problems. I was too self-absorbed during the rehearsals to fully appreciate the order, sensitivity, and preparedness of JoAnn and the orchestra. She didn’t just conduct. She inquired and then tended to my wishes even when my wording was clumsy. Be it a bow change, a little softer here, or a bigger rip there, etc. The work is as hard as new symphonies can be. The entire orchestra of nearly one hundred men and women didn’t flinch. From the podium, her face stern and tender, radiated ease and control over the unfamiliar. Almost as if she simply wanted to be helpful. At some point, she said to me:

"Your symphony is so full of color. I just love it." - JoAnn Falletta

Just like that, at long last, my Muses reappeared. On February 10th 2018, my twenty-eighth year of becoming a composer, they showed up for me to see. The very Muses who had commanded me to write this symphony years before. I saw them nodding from above the balcony. Listen to the BPO performance.

First I bowed to thank the orchestra for their impeccable performance. Then I bowed to the audience for giving it an attentive first listen. With the entire auditorium as my witness, I took my time on stage and I bowed to the Muses. One extra bow.

During intermission, I found the nearest restroom and I wept. After a decade of revising, I finally heard it, my “Symphony No. 1.” I heard in it, its full breath. It was nowhere near its ideal form when the Muses had first delivered it. A sixth revision would have to be underway soon. But I loved it. It was full of life. And I was proud to be in its presence.

Before BPO, “Symphony No.1” had gone through four revisions. The Curtis Symphony Orchestra, American Composers Orchestra, and Minnesota Orchestra have all performed it. These orchestras weren’t in Buffalo that week but they were present when JoAnn placed the first downbeat of my symphony. The Muses appeared not because I did anything different. They came because the input of four orchestras over time lifted the symphony above a certain threshold. It’s not perfect but it’s good enough. My rib cage is gone, so the Muses can meet me heart to heart. And my heart was humming in rapture. I, too, experienced what great composers have experienced over the centuries. Even me, this Shanghai-looking girl.

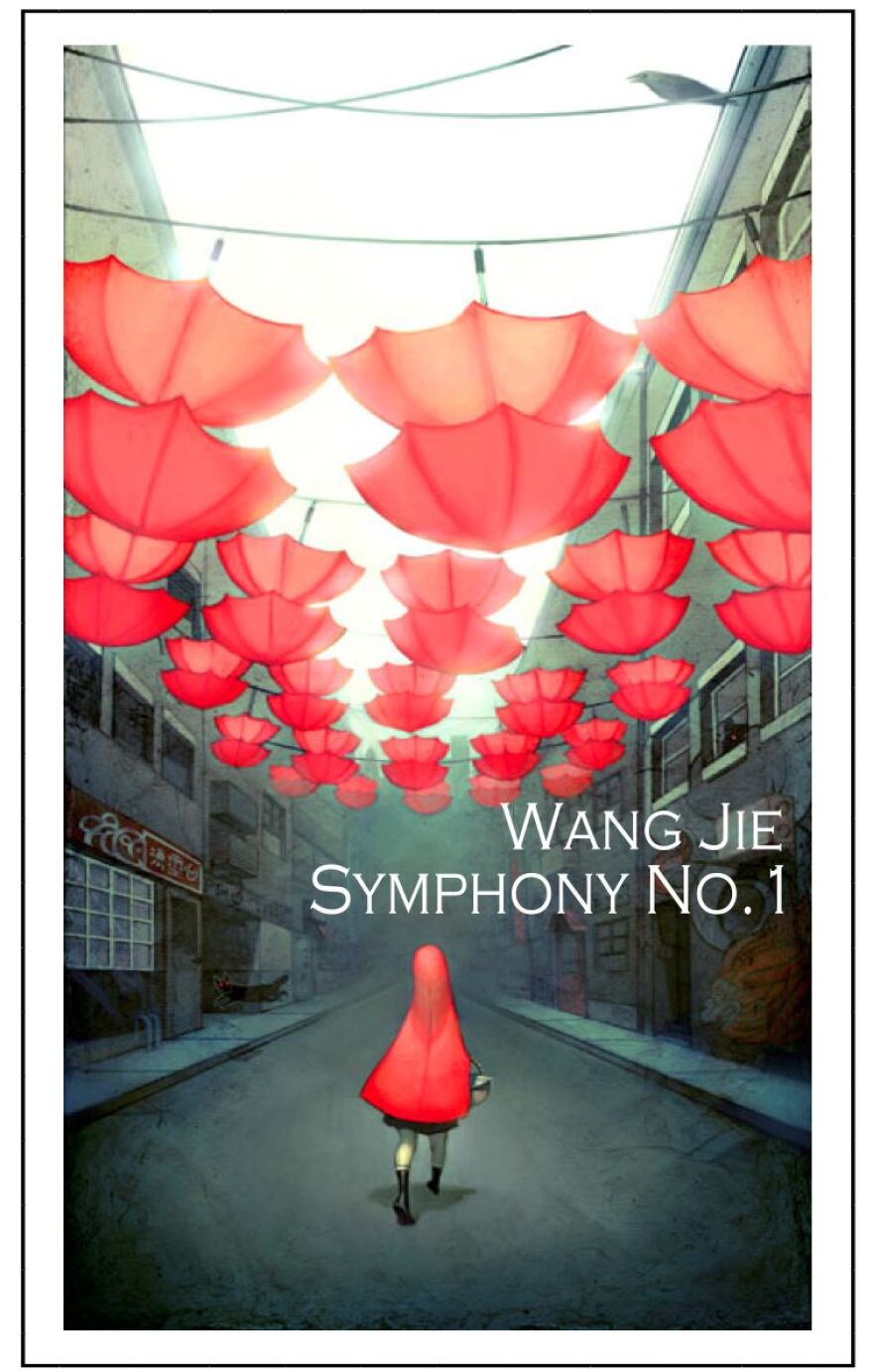

Yang Liqing passed away several years ago. He would have been proud of my fifth revision of “Symphony No.1.” The last time I saw him, he giggled at the cover of that score, an image of upside down umbrellas hanging from the sky. “The cover is the prettiest thing in here,” he said. “The music is not substantial enough to call it a symphony. Brush up your brass writing. And revise it.” That was hard to hear but he was right. I’m compelled to advise: Stay away from 125th Street, free drugs, and camels. Show up to your first rehearsal with ribs, resilience and grit. Revise. Start a new piece. And revise some more. There, now you know almost everything I know about becoming a composer.